Suspicious and associated with witches is probably what most people think about how medieval Europeans viewed cats. While some cats were viewed in this way during the Middles Ages, many people living in Europe during this time also held positive views when it came to felines.

General medieval European views towards cats

Attitudes and beliefs in medieval Europe centered largely around religious beliefs and the teachings of the Church. Overall, people in this time were guided by the belief that God had given them dominion over all the animals. The concept of love or bond with animals was viewed as unnatural and was discouraged.

Superstitions about animals also further dictated how people viewed animals. Especially with dark cats, the concept was pushed that these types of animals were aligned with the devil. Edward, the Duke of York, wrote in the oldest English book on hunting about wild cats, “if any beast had the Devil’s spirit in him, without doubt it is the cat.”

Cat ownership was functional in medieval Europe

Yet, even with these enduring negative attitudes towards felines, cats held a functional value for medieval Europeans. Cats were commonly kept as mousers, both in private homes and at religious institutions.

Cats were used to keep rodents away from grains and eating communion wafers stored in churches. Cats were commonly kept in monasteries and convents to control pests such as mice.

Medieval manuscripts reveal a fondness towards cats

The proximity of cats to humans helped to break that veil of animosity towards them by some. An Irish monk wrote endearingly of his cat, Pangur Bán in an anonymous poem during the early Medieval period. Pangur Bán is an old Irish word meaning ‘fuller white’.

In the poem, the monk compares the way he and his cat work to the way two scholars work, with the monk studying and writing, and the cat hunting and playing. The poem is a straightforward description of the pleasures of intellectual pursuit and the companionship of a pet that existed in medieval times.

Written in the 9th century, the poem is preserved in the Reichenau Primer manuscript (Stift St. Paul Cod. 86b/1 fol 1v).

Medieval riddle about cats

Aldhelm, the early Medieval Abbot of Malmesbury Abbey and the Bishop of Sherborne who was later named a saint by the Catholic Church, published over 100 riddles in his time. On such riddle from Aldhelm involves cats (LXV. Muriceps).

The translation

A fitting custodian in vigilantly guarding the house,

Translation: © G.T Dempsey, Oxford, 1972

I prowl blind coverts through the dark night,

Hardly losing any of the acuteness of my eyes amidst the darkened halls.

For the unseen thieves who ravage the corn bins,

I silently lay out, in ambush, the snares of death.

A wandering huntress, I search out the lairs of these beasties.

I do not will to pursue a fleeing prey with dogs

Who, barking, would turn on me in a savage attack.

A hateful race stuck their lasting name on me.

Examples of cats in medieval manuscripts

During the Middle Ages, many manuscripts were created in monasteries and convents across Europe, and these manuscripts often contained illustrations of everyday life, religious subjects, and other themes including animals and pets.

There are several medieval manuscripts that mention or depict cats. Here are a few notable examples:

The Aberdeen Bestiary is a 12th-century illuminated manuscript that contains descriptions and illustrations of various animals, including cats. The manuscript describes cats as being stealthy and agile predators that are skilled at hunting mice and other small animals.

The Tacuinum Sanitatis is a 14th-century illuminated manuscript that provides advice on health and wellness. It includes a section on cats, which are depicted as being beneficial to humans because they help control the population of mice and other pests.

The Book of Kells is an illuminated gospel book that was created in the 9th century. It includes several illustrations of cats, including one in which a cat is depicted chasing a mouse.

The Ashmole Bestiary is a 13th-century illuminated manuscript that contains descriptions and illustrations of various animals, including cats. The manuscript describes cats as being intelligent and agile, and it suggests that they can be trained to perform tricks.

The Luttrell Psalter is a 14th-century illuminated manuscript that includes several illustrations of cats. One illustration depicts a cat playing with a mouse, while another shows a cat hunting a bird.

Overall, medieval manuscripts often depicted cats as being useful for hunting pests, and they were sometimes described as being intelligent and agile.

Medieval manuscript cats

Here are some drawings and marginalia of cats in other medieval manuscripts.

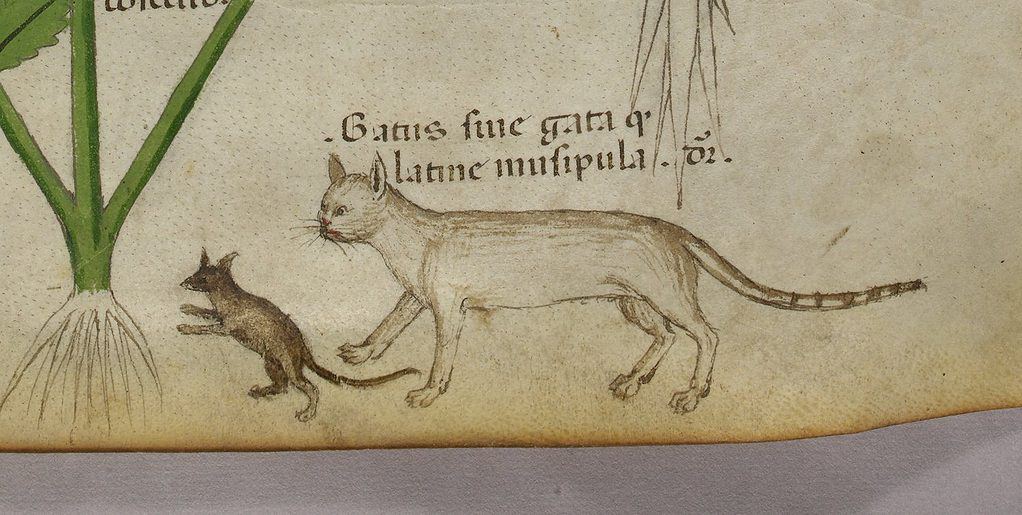

This line drawing at the bottom of a page from an Italian herbal manuscript shows a cat stalking a mouse who is going after one of the plants.

Medieval marginalia of a nun in the act of spinning thread while her cat toys with the spindle.

References

Howe, N. (1985). Aldhelm’s Enigmata and Isidorian etymology. Anglo-Saxon England, 14, 37-59.

Killacky, M. S. (2022, December 23). Cats in the Middle Ages: What medieval manuscripts teach us about our ancestors’ pets. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/cats-in-the-middle-ages-what-medieval-manuscripts-teach-us-about-our-ancestors-pets-195389

Thomas, R. (2005). Perceptions versus reality: changing attitudes towards pets in medieval and post-medieval England. Bar International Series, 1410, 95.

Thornbury, E. (n.d.). Aldhelm’s cat. Stanford Humanities Today. https://shc.stanford.edu/arcade/interventions/aldhelms-cat